Introduction

The use of mandatory post-vest holding requirements on restricted stock awards and restricted stock units ("RSUs") is increasingly prevalent as companies search for ways to strengthen the link between compensation and shareholder interests. Mandatory holding periods typically prevent employees from selling vested equity until additional requirements are meet— usually "owning" shares for one, two or three years following the original vesting date. And in some cases, holding periods can stretch until retirement. By virtue of obliging employees to hold vested equity, companies can achieve a long list of governance benefits, including the achievement of executive ownership guidelines and building a culture of long-term equity ownership.

However, as it turns out, these important benefits are just the starting point on a long and very rich value chain. Mandatory post-vest holding requirements can carry significant additional value for companies and employees, and in many cases, these advantages are never fully realized. These benefits include positive impacts on equity compensation expense, employee tax treatments, and the enforceability of clawback policies, among other items. In the following article, we examine the full scope of benefits offered by mandatory post-vest holding requirements and present practical advice for staying on the right path to unlocking maximum value from your company’s investment in equity compensation.

The Hidden Value of Mandatory Post-Vest Holding Requirements

As we note in our opening remarks above, mandatory post-vest holding requirements are a powerful corporate governance tool, which generate a long list of compelling benefits for companies and employees. To be more specific, these benefits include:

- Defining a Clear Path to Meet Ownership Guidelines

Most C-level executives and many vice presidents are now required to maintain minimum levels of stock ownership in their companies. In fact, recent survey data from Aon Hewitt indicates that stock ownership guidelines have been adopted by 94% of respondents, with most executives required to own equity valued at between two and five times their annual base salary.i Mandatory post-vest holding requirements, when designed correctly to align with ownership targets, can directly contribute to and accelerate the achievement of required ownership levels.

- Creating Practical Mechanisms to Recover Awards via Clawback Policies

After the passage of the Dodd Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act ("Dodd-Frank") in 2010, a growing number of companies adopted clawback policies to recover compensation in the event of governance or financial failings. And once final Securities and Exchange Commission ("SEC") rules are in place, all listed companies will be required to adopt policies providing for the recoupment of compensation in the event of an accounting restatement. Mandatory holding periods for vested equity awards are one of the few realistic practices that companies can employ to make clawback mechanisms feasible. How? They allow for easier recovery of awards after they are vested or "earned" because employees are forced to hold onto shares for an extended period of time.

- Promoting Greater Alignment with Shareholder and Proxy Advisor Policies

Institutional investors and proxy advisory firms view mandatory post-vest holding requirements in a favorable light. For example, Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS) recently updated its equity plan evaluation methodology to include positive scoring for mandatory holding periods and ISS views the use of holding periods as a risk mitigating pay practice for its Say-on-Pay evaluations. Similarly, Glass Lewis & Co. also rates the presence of equity holding periods positively in their equity plan evaluation framework.

- Improving the Tax Deductibility of Time-Vested Restricted Stock and RSUs

Section 162(m) of the Internal Revenue Code imposes limits on the tax deductibility of compensation paid to named executive officers ("NEOs") that is not considered performance-based. However, these limitations do not apply to compensation paid after an individual is no longer an NEO. Deferring the distribution of shares underlying a restricted stock award or delaying settlement of an RSU until after a recipient is no longer an NEO can serve as a method to ensure the full tax deductibility of time vested awards. Holding periods that stretch until retirement can help achieve this aim.

- Preserving Preferred Tax Treatment for ISOs and ESPPs

Section 423 of the Internal Revenue Code requires incentive stock options ("ISOs") and shares issued under employee stock purchase plans ("ESPPs") to be held by employees for a specified period of time in order to retain advantageous tax treatments. Post-vest holding periods, assuming they are long enough in scope, can increase an award’s tax qualified status by prohibiting sales that might otherwise result in a disqualifying disposition.

- Reducing Compensation Expense under ASC Topic 718 and IFRS 2

Current accounting requirements in the US and abroad require companies to reflect post-vesting conditions (i.e., mandatory holding requirements) in the initial grant date valuation of awards. In the US, Accounting Standard Codification Topic 718 ("ASC Topic 718") states that "the restrictions and conditions inherent in equity instruments awarded to employees are treated differently depending on whether they continue in effect after the requisite service period. A restriction that continues in effect after an entity has issued instruments to employees, such as the inability to transfer vested equity share options to third parties or the inability to sell vested shares for a period of time, is considered in estimating the fair value of the instruments at the grant date." Similarly, International Financial Reporting Standard 2 ("IFRS 2") provides that "if the shares are subject to restrictions on transfer after vesting date, that factor shall be taken into account, but only to the extent that the post-vesting restrictions affect the price that a knowledgeable, willing market participant would pay for that share." Applying a "discount for illiquidity" to award valuations is a common technique, with both empirical and theoretical backing, that firms can use to reduce compensation expense under the accounting standards cited above. The remainder of our article examines this very issue.

Key Financial Accounting Considerations

Looking at the final bullet point above, we’d like to spend a good deal of time exploring how companies can achieve equity expense cost savings from mandatory post-vest holding requirements. It’s a complex process, but it is critical to realizing both the governance and financial benefits of holding periods.

If you examine relevant financial accounting literature – US GAAP and IFRS in this case – you’ll see that it provides guidance affirming the ability to apply a "discount for illiquidity" against the fair value of an award or stock compensation when a holding requirement prohibits the sale of the underlying stock and remains in force for a period of time after the award is vested. However, there are two important criteria that must be satisfied before a mandatory post-vest holding requirement can be used to reduce the estimated fair value of the award.

First, the restrictions created by the holding requirement must be an attribute of the specific award in question. In other words, if award agreements and/or plan documents include an absolute prohibition on the sale of shares underlying the award for a period of time after the award has vested, it is appropriate to apply a discount to reflect the post-vest period of illiquidity. On the other hand, a discount for illiquidity cannot be applied to reflect restrictions or limitations that are imposed on the employee, but are not a feature of the specific equity award. For example, let’s assume that a company requires all vice presidents to own 20,000 shares of common stock. Due to the fact that this stock ownership requirement is specific to employees (i.e., all executives at the vice president level) a discount for illiquidity can not be applied to shares used to satisfy ownership guidelines. However, if the same company grants vice presidents RSUs that include a mandatory post-vest holding requirement within plan documents, it is appropriate to include a discount for illiquidity because the restrictions are now a documented feature of the award and not solely an attribute of the employee— regardless of whether the RSUs were counted towards each vice president’s respective stock ownership guideline.

The second condition that must be satisfied is that the restriction must represent an absolute prohibition on sale, rather than a limitation on an employee’s ability to sell the stock. For example, publicly traded companies sometimes issue shares of stock that are not been registered with the SEC. These unregistered shares are referred to as Rule 144 stock (Rule 144 stock can also be called "letter stock"). Rule 144 stock cannot be sold in the open market during a six month period following its issuance. However, during the six month period, Rule 144 stock may be sold to qualified investors in a private transaction. The SEC has issued guidance stating the requirements of Rule 144 represent a limitation on the ability to sell the stock, but not a full prohibition on sale. As a result, the SEC does not allow the application of a discount for illiquidity on Rule 144 stock.

Methods for Quantifying the Impact of Illiquidity

Once it is determined that the mandatory post-vest holding requirement in question is an attribute of the award, not a function of the holder, and serves as an absolute prohibition on a sale, not a partial one, the impact of the post-vest holding period can be quantified for the purposes of reducing equity compensation expense. There are two fundamental approaches for developing the estimated value of a discount for illiquidity: (1) empirical methods based on observable data and (2) various quantitative models backed by rigorous testing.

Empirical Methods

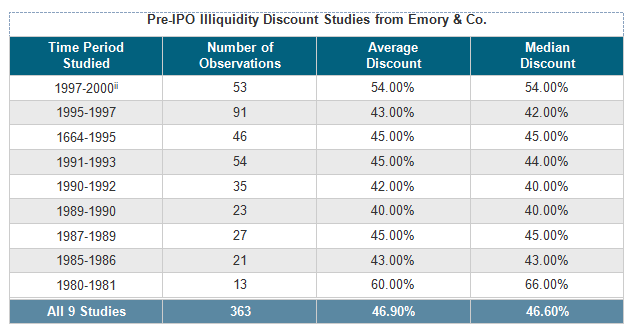

One of the most accessible resources for gathering market data on the magnitude of illiquidity discounts is to observe the price at which a company completes its initial public offering ("IPO") relative to the price at which it is traded shortly before an IPO. Emory & Co. conducted several prominent studies on this type of data, showing that discounts for illiquidity can easily approach 50% of fair market value. The following table summarizes multiple Emory & Co. analyses on illiquidity discounts implied by pre-IPO transactions.

However, in reviewing the data above, we must note that a majority of pre-IPO stock price information is based on the exercise price of employee stock options, rather than actual transactions in the underlying stock. As a result, pre-IPO stock prices tend to represent a management team’s estimate of the fair value of stock for the purposes of ASC 718 and § 409A compliance. These prices may not necessarily reflect a true market value, which can potentially skew assessments of illiquidity discounts.

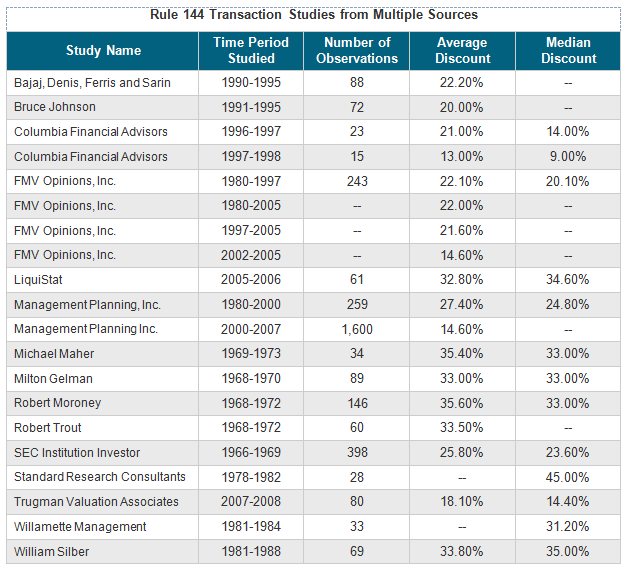

A second source of empirical data can be developed from transactions in unregistered shares of stock. As we note in the "Financial Accounting Considerations" section above, Rule 144 of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 prohibits shares of stock that have not been registered with the SEC from being sold in an open market transaction during the six months immediately following issuance. However, on occasion, publicly traded companies that wish to raise capital, but don’t wish to go through the underwriting process for a secondary offering, issue a large block of unregistered shares to an institutional investor, such as a hedge fund, in a private transaction under Rule 144. This type of transaction is known as a private investment in public equity, or PIPE transaction. Due to the fact that shares issued via a PIPE transaction are identical to regular company stock traded on public exchanges, except for the six month Rule 144 restriction, a discount for illiquidity can be developed by comparing the per share price in the PIPE transaction to the price of the company’s stock in the open market at the time the PIPE transaction was completed.

A large number of studies on Rule 144 transactions were conducted over the years to quantify the discount demanded by market participants for assuming the additional risk inherent in illiquid stock. The table summarizes results from 20 of the most robust research efforts, and shows average discounts ranging from between roughly 15% and 35% of fair market value.

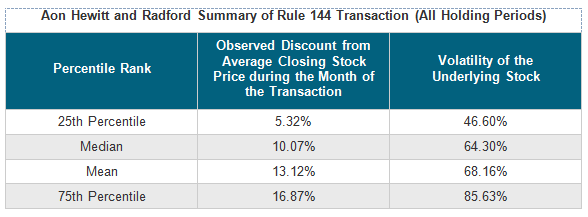

To gain additional insight on the size of illiquidity discounts, and the key factors that might impact the value of discounts, we conducted our own analysis of Rule 144 stock transactions.iii The table below summarizes our observed discounts from all transactions pursuant to Rule 144 stock included in the BVR Resources - FVM Opinions database, regardless of holding period.iv We also cite the volatility of the underlying stock related to Rule 144 transactions to begin highlighting the role that volatility plays in illiquid discount outcomes. v

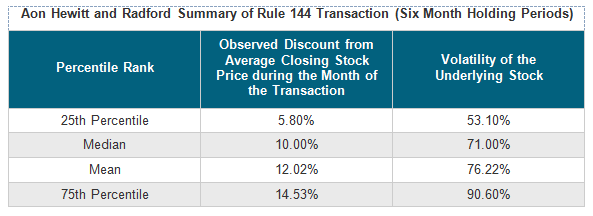

We also examined observed discounts for all Rule 144 stock transactions included in the BVR Resources - FVM Opinions database after required holding periods were reduced from one year to six months.vi Again, volatility information was also collected.

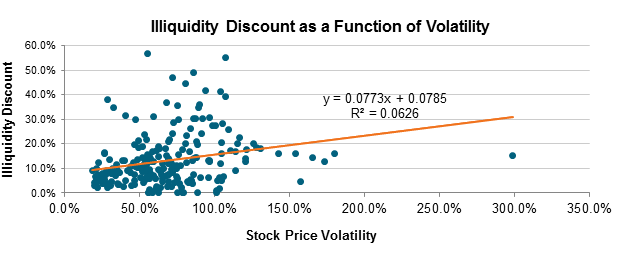

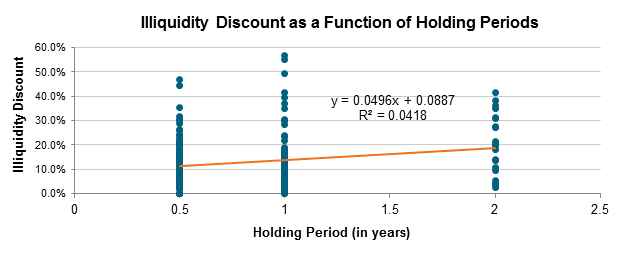

As is illustrated in the tables above, two of the key factors impacting the value of discounts for illiquidity are the volatility of the underlying stock and the duration of the holding period. The size of the illiquidity discount is positively correlated with the volatility of the underlying stock, with market participants requiring a larger discount to compensate them for the additional risk of higher volatility shares. The size of the discount also increases with longer holding periods. When reviewing this data, please note that the outside studies on pre-IPO and Rule 144 transactions we cite above only list midpoint outcomes – either an average or median discount – whereas our data highlights a broad range of potential outcomes.

When developing an estimated illiquidity discount for a mandatory holding requirement, significant consideration must be given to where within the range of observed discounts a particular company might be positioned. With this in mind, the SEC has stated that it is "not enough to simply cite the average marketability discount used by your investment banker or to highlight that the amount of the discount used falls within a broad range you noted in an academic study. As a starting point in evaluating these discounts, we try to understand the duration of the restrictions and the volatility of the underlying stock. Generally, the longer the duration [of the restriction] and the higher the volatility, the higher the discount [will be]." vii As a result, it is not acceptable to simply base your estimated illiquidity discount on a rule-of-thumb.

Quantitative Models

As you likely noticed, there are significant variations in the results of the studies discussed above, with the average observed discounts for illiquidity ranging from a low of 13.0% to a high of 60.0% across all outside studies. Additionally, there is not a great deal of clarity on the differences among companies included in these studies that might allow for a more detailed apples-to-apples comparison of data points to develop a specific illiquidity discount estimate for your company. Given the limitations of using composite survey data, as well as the sensitivity of illiquidity discounts to the length of the holding period and the volatility of the underlying stock, a more common approach is to estimate illiquidity discounts using mathematical models that leverage all available empirical datasets.

For our part, we performed a statistical regression analysis to identify where within the range of observed discounts a given company might fall. Based on our analysis of the data for transactions in the Rule 144 stock, the coefficients for volatility and holding period are statistically significant. The chart below illustrates the observed illiquidity discount as a function of the volatility of the underlying stock.

The size of the illiquidity discount also increases with the length of the holding period. The chart below illustrates the illiquidity discount as a function of the length of the holding period.

Additionally, academic researchers and valuation practitioners have developed various quantitative models to estimate illiquidity discounts. Four of the most common quantitative methods include:

- Collared Strategy ("Cost of Carry")

Under this approach, the cost of illiquidity is assumed to equal the opportunity cost of not being able to sell the underlying stock and pursue alternative investments. This approach has the benefit of being simple and straightforward to implement, as the amount of the illiquidity discount equates to the risk-free rate of return over the holding period. However, the drawbacks of this approach typically outweigh its ease of use. First, this approach does not capture the additional risk inherent in being required to hold a share of stock relative to holding a risk-free bond (i.e., the technique ignores volatility). Moreover, the discounts produced by this approach consistently understate the cost of illiquidity when compared to empirical data. The Cost of Carry collared strategy is not commonly used in practice.

- Chaffe Protective Put Method

The Chaffe method was the first approach for assessing illiquidity discounts based on an option pricing model, and serves as the foundation for other option pricing model-based methods. Under the Chaffe method, the cost of illiquidity is assumed to equal the cost of an at-market put option with a contractual term equal to the duration of the mandatory post-vest holding period. Intuitively this approach makes sense because the holder of an illiquid security could theoretically obtain liquidity by exercising the put. A common criticism of the Chaffe method is that the purchase of an at-market put option provides a second benefit in addition to liquidity. An at-market put option will also hedge away downside risk by providing a fixed price below with the value of the stock cannot decline. However, as noted in the AICPA Practice Aid Valuation of Privately-Held-Company Equity Securities Issued as Compensation, "the protective put method should not be considered to represent an actual transaction but rather, to represent a reasonable regression-based fit to the discounts observed in restricted stock data." That is, the validity of the model rests in its ability to produce estimated illiquidity discounts that are consistent with the discounts observed in the market. As a result, the Chaffe protective put method is commonly used in practice.viii

- Longstaff Model

Under the Longstaff model, the cost of illiquidity is based on the value of a "look-back" option at the end of the restriction period, as opposed to Chaffe’s approach, which bases the illiquidity discount on the value of the option at the beginning of the restriction period. A look-back option allows the holder to sell the underlying stock at the highest price during the restriction period. In contrast to the Chaffe protective put method, in which the objective is to estimate the amount required to eliminate potential losses during the holding period, the objective of the Longstaff model is to estimate the maximum amount of profit the holder was required to forego as a result of not being able to sell the underlying stock. As a result of basing the illiquidity discount on the maximum amount of foregone profit, the Longstaff model implicitly assumes the holder of the illiquid stock possesses the ability to perfectly time the market. Due to the fact that most investors do not possess perfect market timing ability, the Longstaff model tends to overstate the magnitude of the illiquidity discount. For this reason, the Longstaff model is not commonly used in practice, except for very low volatility stocks.ix

- Finnerty Model

When using the Finnerty model, the cost of illiquidity is assumed to equal the cost of a put option with a strike price that is based on the average stock price over the option’s term (this type of option is sometimes called an Asian put option). The use of an average strike price option eliminates the issue of perfect market timing inherent in the Longstaff model and the issue of hedging away the downside risk inherent in the Chaffe method. However, as Dr. Finnerty noted in the paper accompanying the 2012 update of the model, this approach tends to understate the discount for lower volatility stocks. By virtue of addressing common complaints associated with the quantitative models cited above, the Finnerty model is commonly used in practice. x

Making the Leap to Valuing Mandatory Post-Vest Holding Requirements

In the section above, we discussed how academics and investors use empirical data and quantitative models to assess illiquidity discounts related to pre-IPO and Rule 144 transitions, which typically cover sales restrictions of one year or less. However, returning to the issue of mandatory post-vest holding requirements for equity awards, our clients typically need effective models covering periods of one year or more.

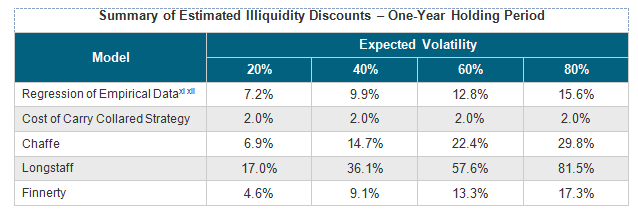

Using our regression data of Rule 144 stock transactions, as well common quantitative models, we developed a range of potential illiquidity discounts by volatility levels covering longer periods of time. These ranges will help companies make the practical leap of assessing the potential value of attaching mandatory post-vest holding requirements to future equity awards. In the first chart below, we display estimated discounts for the lack marketability of vested stock awards with a one-year holding period:

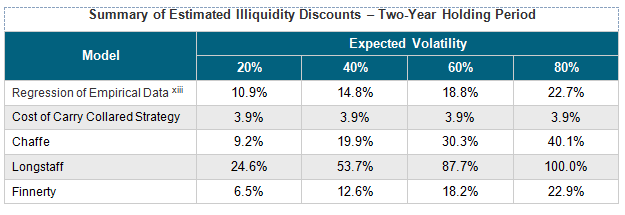

In the next chart, we display estimated discounts for the lack marketability of vested stock awards with a two year holding period:

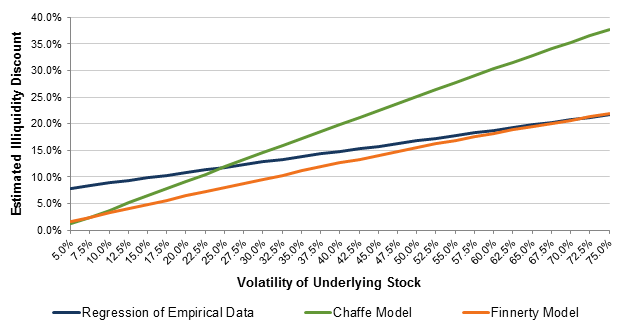

As expected, there is significant dispersion between estimated illiquidity discounts, with the estimated discounts produced by the Cost of Carry collared strategy and the Longstaff model serving as outliers. The illiquidity discounts produced by our internal regression analysis, the Chaffe method, and the Finnerty model are more tightly clustered. The chart below illustrates the estimated illiquidity discounts produced by our internal regression analysis, the Chaffe method, and the Finnerty model under a range of volatility assumptions.

Considerations when Developing an Illiquidity Discount

The development of the estimated illiquidity discount should be based on each company’s individual facts and circumstances and the features of the underlying equity award. From a valuation perspective, there are three objectives that must be satisfied when selecting a model to develop the estimated illiquidity discount. First, the illiquidity discount produced by the model must be consistent with discounts observed in the market. Second, the model should produce greater discounts for higher volatility stocks. Third, the model should produce greater discounts for longer holding periods.

The validity of the model used to develop the estimated discount for lack of marketability is dependent on the satisfaction of these three criteria. A common criticism of option pricing model-based approaches for estimating a discount for lack of marketability is that the models conceptually overstate the discount because the purchase of a put option also hedges away downside risk. However, we note that within the relevant range of volatility, the discounts produced by the Chaffe method and Finnerty model match observed market discounts. As a result, we view this criticism as irrelevant in this case.

A further consideration for developing estimated illiquidity discounts is that mandatory post-vest holding periods represent an absolute prohibition on sales, while restrictions on Rule 144 stock only represent a limitation on the number of potential buyers during the restriction period. The quantitative models were developed and calibrated using transaction data for Rule 144 stock. In theory, the discount a market participant would require for a share that is subject to a mandatory holding period would exceed the discount for Rule 144 stock. As a result, it may be appropriate to select a discount that is slightly above the discount developed using a quantitative model or at the higher end of the range if more than one model is used.

A best practice would be to consider the estimated illiquidity discount produced by each model and ultimately rely on the model or models that are most appropriate given the individual company’s facts and circumstances.

- The Cost of Carry collared strategy typically will not be reliable because it violates a core principle that the discount should increase with increases in expected volatility assumption.

- Reliance on the Longstaff model is limited because the estimated illiquidity discounts typically exceed, sometime greatly exceed, discounts observed in the market. The use of the Longstaff model should typically be limited to very low volatility stocks.

- Depending upon the volatility of the underlying stock and the length of the holding period, the discount produced by the Chaffe protective put method and/or the discount produced by the Finnerty model will likely be most reliable.

- Greater weight may be placed on the discount produced by the Finnerty model for stocks with volatility between 45% and 75%. In the paper discussing the 2012 revision to the model, Dr. Finnerty stated that model-predicted discounts understate the magnitude of the illiquidity discounts observed in market transactions for stocks with volatility below 45% or above 75%

- Greater weight may be placed on the discount produced by the Chaffe method for stocks with volatility below 45%

Based on the totality of the data, the concluded illiquidity discount may be based on the results of a single model, or a relative weighting of the results of multiple models. Regardless of the model or models that are selected, the concluded illiquidity discount must reconcile with the discounts observed in the market.

Conclusion

Given the current corporate governance environment and strong institutional investor preferences in favor of mandatory holding requirements for vested equity awards, we expect post-vest holding periods to grow in prevalence significantly over the next three to five years. While all companies will achieve some benefits from adopting mandatory holding requirements, others could easily miss a number of significant advantages associated with mandatory holding requirements. This is especially true when it comes to determining complex illiquidity discounts.

Companies need to be thoughtful and deliberate when selecting the model or models they will use to estimate illiquidity discounts for purposes of ASC 718 or IFRS 2. Relying on anecdotal data or rules of thumb will not pass muster with auditors or the SEC. While significant effort is required, when properly developed, illiquidity discounts allow companies to reduce equity compensation expense at the same time as they strengthen corporate governance.

To learn more about the full set of governance and accounting benefits associated with mandatory post-vest holding requirements, please visit holdaftervest.com.

To learn more about participating in a Radford survey, please contact our team. To speak with a member of our compensation consulting group, please write to consulting@radford.com.

i Source: Aon Hewitt US Total Compensation Measurement (TCM) Survey of Executive Compensation Policies and Programs 2013.

ii Explanatory Note: This period of the Emory & Co. study covers "dot-com" companies.

iii Explanatory Note: Based on transaction information available through October 1, 2014.

iv Explanatory Note: When adopted in 1972, Rule 144 initially required a two year holding period. In 1997, the restriction period was shortened to one year. In 2008, the restriction period was further shortened to six months.

v Explanatory Note: The observed illiquidity discount and the volatility summarized in the table above relate to the same the Rule 144 stock transaction. For example, the volatility of the stock underlying the Rule 144 stock transaction with the median discount of 10.07% equaled 64.30%.

vi Explanatory Note: Based on information available through October 1, 2014.

vii Source: Todd Hardiman, Associate Chief Accountant, Division of Corporation Finance. Speech by SEC Staff: 2004 Thirty-Second AICPA National Conference on Current SEC and PCAOB Developments. http://www.sec.gov/news/speech/spch120604teh.htm

viii Source: David B. Chaffe, "Option Pricing as a Proxy for Discount for Lack of Marketability in Private Company Valuations," Business Valuation Review 12(December 1993): 182-88.

ix Source: Francis A. Longstaff, "How Much Can Marketability Affect Security Values," The Journal of Finance 50 (December 1995): 1767-74.

x Source: John D. Finnerty, "An Average-Strike Put Option Model on the Marketability Discount," The Journal of Derivatives 19 (Summer 2012) 53-69.

xi Explanatory Note: Based on information available through October 1, 2014.

xii Explanatory Note: Based on the results of the statistical regression analysis of transactions in Rule 144 stock with a one year restriction period, the estimated illiquidity discount equals 4.35% + 14.1% * Volatility.

xiii Explanatory Note: Based on the results of the statistical regression analysis of transactions in Rule 144 stock with a one year restriction period, the estimated illiquidity discount equals 6.9% + 19.8% * Volatility.

Related Articles