"When you win [with options], you win the lottery. And when you don't win, you still want it. The fact is that the variation in the value of an option is just too great. I can imagine an employee going home at night and considering two wildly different possibilities with his compensation program. Either he can buy six summer homes or no summer homes. Either he can send his kids to college 50 times, or no times. The variation is huge; much greater than most employees have an appetite for. And so as soon as they see that options could go both ways, we proposed an economic equivalent. So what we do now is give shares, not options." — Bill Gates (2003)

Bill Gates' perspective is one that technology companies have fully recognized for ten-plus years: stock options can be very volatile. And since employers typically assume that employees shy away from volatility in their pay outcomes, the competitive value of options in attracting talent has become increasingly questionable.

Over the past ten years, technology companies have migrated away from options-centric equity programs to programs focused on full-value share awards, which include restricted stock, restricted stock units and performance shares, among other vehicles. In the vast majority of cases, and especially for non-executive employees, companies have moved to restricted stock units ("RSUs"), which is the broad term we use throughout this article.

Although this shift from options to RSUs is firmly entrenched and expected to endure for years to come, some companies still question whether this trend is actually the best means for driving innovation and establishing employee ownership. Skeptics of the trend also point out that reducing volatility can sever the alignment between employees and shareholders — a link that options preserve.

This leaves us asking a number of fundamental questions: Do we see a performance trade-off between the use of options and RSUs? And are shareholders and employees worse off or better off when equity is paid in the form of options compared to RSUs? This article examines some of those questions and explores the reasons behind the move toward RSUs.

The Big Switch

When Gates made his statement about options in 2003, the use of restricted stock in the technology sector was highly unusual and somewhat controversial. A couple technology leaders, like Microsoft and Amazon, had raised eyebrows by making the switch from options to restricted stock, but that was it.

Eleven years ago, only 3% of technology companies had RSU-centric equity plans, defined as plans with more than 50% of their equity in the form of restricted stock. Meanwhile, companies issuing only options totaled 90% of the market. The move to RSUs, however, evolved quickly. By 2008, 42% of companies were RSU-centric, and by 2013, nearly three-quarters of technology companies had RSU-centric equity strategies. Today, 42% of companies with RSU-centric plans use RSUs as their sole form of equity.

In contrast, life sciences companies did not accelerate toward RSUs to the same degree. Virtually all life sciences companies were option-centric in 2003, and more than three-quarters of them remained so through 2013. Nonetheless, RSUs play a larger role in life sciences sector equity plans today, with a little over half of companies using full-value shares to some extent.

From our vantage point, both technology and life sciences companies typically incorporate RSUs into the equity mix following an important company milestone. In the technology realm, this milestone is often an initial public offering (IPO); in the case of life sciences firms, it is typically a commercial launch.

The context behind the market's migration to RSUs is important; company choice was not the sole determinate of the trend. Declining employee appetite for stock option volatility played a role, as Bill Gates noted, but so too did significant changes in expensing regulations and successive stock market downturns in 2000 and 2008, which left millions of option grants underwater and worthless in the minds of employees. Among those reasons, Radford data shows the clearest move toward RSUs during the 2008/2009 recession. Prior to 2008, about 35% of technology companies and 6% of commercial life sciences companies were RSU-centric. By 2010, those figures reached upward to two-thirds of technology companies and 15% of life sciences companies, and the trend has climbed steadily since.

Who Actually Wins?

Despite what the data suggests, not everyone is enthusiastic about increased use of RSUs over options. Some critics believe RSUs are just "cash by another name," because they typically payout at the end of a vesting period without performance requirements. The problem, as critics see it, goes back to one of the initial concerns we highlighted: a disconnect between shareholder and employee interests.

Others have more nuanced concerns with RSUs. As one ex-Silicon Valley CEO, who wished to remain anonymous, told our team:

"It used to be that Silicon Valley attracted risk takers from all over the world who were willing to sacrifice cash for an opportunity to hit it big via stock options. We had a culture that encouraged innovation and risk-taking. Now with all the companies using RSUs, and employees essentially working for guaranteed pay, I wonder if we are still attracting the type of people that will spur the level of innovation and performance that made Silicon Valley unique in the first place."

From this individual's perspective, the very risk that Gates found untenable on behalf of employees is precisely what created a successful and innovation-laden culture. In this view, risk and innovation are inseparable, and because that risk is inherent in options and absent in RSUs, RSUs undermine growth potential. Without risk, there can be no innovation, and without innovation there can be no growth.

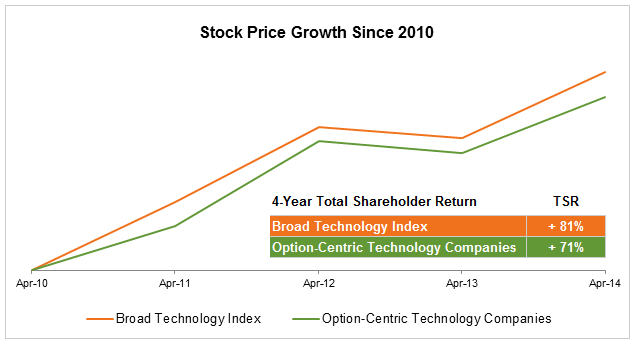

While we won't attempt to measure innovation (others have tried, as we highlight at the end of this article), we did look at the question of performance and the relationship that might exist between performance and equity vehicles. In the chart below, we compare a broad technology index to a group of companies that continue to rely on option-centric programs. Using total shareholder return as our measure of performance, we examined a four-year period between April 2010 and April 2014. In contrast to what some might expect, we found that the broader index outperformed the option-centric companies. Not only did employees at the RSU-centric companies do better, shareholders did as well.

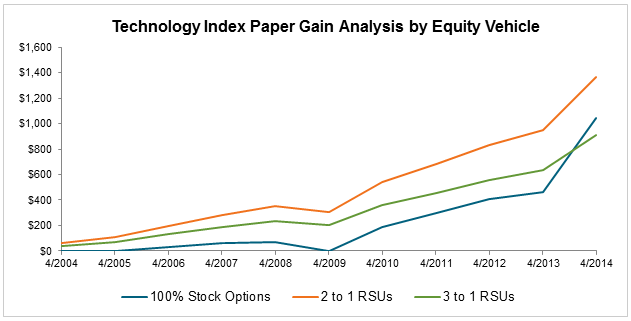

Even over a 10-year period, it appears that employees are slightly better off with RSUs (issued at a 2:1 ratio to options). As the graph below illustrates, using our broad technology index as a basis, both 2:1 RSUs and 3:1 RSUs perform better than options throughout much of the last ten years. Only in 2013, assuming an employee had held their options for a full 10 years, would they have realized similar or more value compared to RSUs.

But of course, timing is everything. The biotechnology industry's incredible growth in stock prices since the 2008 recession means that employees granted 100% options have fared much, much better than employees whose option grants were converted at a 2:1 or 3:1 ratio into RSUs. If you're lucky enough to receive options just before a massive market upswing, the upside potential remains tremendous as ever.

The Wages of Success

From a company's perspective, equity is granted for any number of reasons, but it mainly serves as an important tool in attracting and retaining talent. As we mentioned, part of the reason companies moved to RSUs over the past decade was to make employees more comfortable with their incentive compensation. A company offering RSUs also offers less risk in its total compensation package; thus, RSUs make for a better recruitment and retention tool. However, as RSUs have become more commonplace in the market, the inherent competitive advantage of simply offering them has diminished. This leads to the question of how to design an equity plan with RSUs that continues to make them more competitive than options.

Companies have a few different levers to make their RSU-heavy equity programs stand apart. Some simply spend more, and we see significant variability in the value of grants among different industry sub-sectors and/or geographies. Employees in software companies in the San Francisco Bay Area, for example, receive more than their counterparts in other sub-sectors located outside the Bay Area. Along similar lines, some companies broaden participation to include more employees throughout the organization. By contrast—and in keeping with a broad trend throughout the technology industry—some companies are concentrating more equity value into fewer hands. Key engineering and technical talent groups are typically the beneficiaries, although some companies also look at more diligent use of performance hurdles as equity award triggers.

Finally, some companies are revising their vesting practices, moving from four-year to three-year schedules. To date, technology and biotechnology companies have somewhat different patterns, with about two-thirds of technology companies on four-year schedules, and just under half of biotechnology companies on the this schedule. The 30% to 40% of companies that use three-year or shorter schedules can claim a competitive advantage by driving more value via equity to employees sooner.

Conclusion

The move away from stock options began a decade ago, but we've seen a marked acceleration in the use of RSUs since the most recent economic downturn. While some RSU skeptics worry that equity incentive plans devoid of options divorce the connection between shareholders and employees, or perhaps worse, discourage innovation by reducing risk, there are many advantages of RSUs. These include less volatility in employee compensation, avoiding expense regulations from underwater options, and a potential connection to better shareholder returns, as our research suggests.

The move to RSUs doesn't come without a few words of caution. Currently, we live in an environment where equity programs look homogenous across the market— the same was true in 2000 when complaints about the overuse of options began to accelerate. Whenever observers believe the pendulum of compensation practices swings too far in one direction, concerns tend to emerge. In 2000, it was excessive risk taking and sky-high dilution rates. Today, it is "pay-for-pulse" and a lack of creativity in developing performance measures when they are used. In the past and today, companies face rising pressure to justify the strategy behind their equity choices— simply following the trend is no longer a sufficient explanation for boards, investors and proxy advisors.

In this vein, as the move away from options continues, competing for talent with RSUs- will require more creativity to differentiate equity plans and to develop meaningful employee value propositions. It's a tall order, but companies have time to work it out; we don't expect RSUs to go anywhere anytime soon.

To learn more about Radford's executive compensation, broad-based compensation and compensation governance consulting services, please visit: radford.aon.com/consulting

End Note: Measuring Innovation

For more information on efforts to measure corporate innovation, we recommend starting with these examples here, here and here.

To learn more about participating in a Radford survey, please contact our team. To speak with a member of our compensation consulting group, please write to consulting@radford.com.

Related Articles